Association between Household Income and Asthma Symptoms among Elementary School Children in Seoul

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the association between socioeconomic factors and asthma symptoms.

Methods

A total of 6,919 elementary school children in Seoul were enrolled in the study. Data were obtained from a web-based questionnaire survey. The questionnaire was based on the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood core module. The prevalence of wheeze in the past 12 months and severe asthma symptoms were obtained. The potential risk factors for asthma symptoms included household income and the number of siblings. A multiple logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the risk factors of asthma symptoms.

Results

The prevalence of current wheeze (wheeze in the past 12 months) was 5.2%. Household income and asthma symptoms were inversely associated after adjusting for other potential risk factors (p for trend=0.03). This association was modified by the number of siblings. With two or more siblings, the effect of household income on asthma symptoms was not significant. However, low household income was still a significant variable for patients with fewer than two siblings (OR 1.41; 95% CI, 1.09-1.81).

Conclusions

It appears that childhood asthma disparity is dependent on household income. Therefore, policies to improve childhood health inequities should be emphasized.

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases in childhood and imposes a substantial socioeconomic burden [1]. According to a nationwide survey, the prevalence of asthma among school-age children was reportedly 7.6% [2].

The etiology of asthma is considered to be multifactorial. In addition to genetic susceptibility [3], environmental factors, such as passive smoking, play an important role in the development and severity of asthma [4]. In addition, other factors, such as socioeconomic status (SES) and the number of siblings, have been evaluated recently.

Previous investigations have shown that SES is associated with children's health, including asthma [5,6]. Rona reported that poverty may affect asthma as an etiological factor and/or a factor contributing to the exacerbation of the condition [7]. Asthmatic children with low SES seem to experience more asthmatic episodes, more hospitalizations, and more severe symptoms compared with those children with high SES [8,9].

Previous studies reported that having more siblings protects against allergic diseases. In the literature, this phenomenon has been described as the "sibling effect". In their systematic review article, Karmaus and Botezan reported that 22 of 31 studies reported a negative association between asthma and the number of siblings [10]. These findings were mostly from Europe. In Korea, Yang et al. [11] reported that having no older siblings was a risk factor for persistent wheezing in infants. However, except for the Yang study, there have been few investigations about the sibling effect on asthma.

In this study, we investigated the prevalence of asthma symptoms and examined the association between socioeconomic factors and asthma symptoms in elementary school children of Seoul. Additionally, we examined the interaction between the sibling effect and socioeconomic status on asthma symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Subjects were recruited from the "Seoul Atopy Free School" as part of the "Atopy Free Seoul Project." In 2009, 83 institutions participated in the project (62 kindergartens, including day-care centers, and 21 elementary schools). We informed those institutions about the purpose of the study, and 10,431 children from 23 institutions (12 kindergartens and 11 elementary schools) agreed to participate in the survey. The parents or guardians of the children provided informed consent, and volunteers registered via a website. In total, 8,780 subjects participated (response rate=84.2%). Preschool children were excluded (n=1,241), and of the remaining 7,539 elementary school children, those who did not answer one or more survey questions were also excluded (omitted individual variables, such as birth weight, n=358 and omitted environmental variables, such as housing information, n=265). Finally, 6,916 subjects were included in the analysis.

Questionnaire Survey

A web-based survey was conducted from June to October, 2009, via the Seoul Asthma Atopy Education Information Center website (http://www.atopyinfocenter.co.kr). The questionnaire was completed by the parents or guardians of the subjects. The questionnaire was based on the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) core module [12]. Using the official Korean version of the ISAAC questionnaire, data about asthma symptoms were obtained. In addition, data about demographic characteristics, environmental factors including household income were also obtained using an additional questionnaire. Average monthly household income was categorized into three levels: <2 million Korean won (KRW) per month, between 2 and 4 million KRW per month, >4 million KRW per month. To adjust for family size, the number of family members was obtained.

Definition of asthma symptoms

Based on the ISAAC criteria, the prevalence of wheeze in the past (wheeze, ever), wheeze in the past 12 months (current wheeze), sleep disturbance from wheeze in the past 12 months, and speech limited by wheeze in the past 12 months were obtained. The following questions were asked: 1) Has your child ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest at any time in the past? (wheeze, ever); 2) Has your child had wheezing or whistling in the chest in the past 12 months? (current wheeze); 3) In the past 12 months, has your child's sleep been disturbed because of wheezing? (sleep disturbance from wheeze in the past 12 months); 4) In the past 12 months, has wheezing ever been severe enough to limit your child's speech to only one or two words at a time between breaths? (speech limited by wheeze in the past 12 months).

Severe asthma symptoms were defined if the subjects had one or more of following 3 conditions: 1) sleep disturbance from wheeze; 2) speech limited by wheeze; 3) absence due to asthma symptoms.

Statistical analysis

A frequency analysis was performed for the categorical variables. Chi-squared tests were performed to analyze the association between current wheeze and relevant factors. Trend tests for ordinal variables were performed. A multiple logistic regression analysis was applied to calculate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the potential risk factors for current wheeze, with adjustment. In the multiple logistic regression analysis, models both with and without interaction terms between the number of siblings and household income were conducted. The same method was applied to analyze the association between the severe asthma symptoms and potential risk factors. The SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. The results were considered statistically significant if p values <0.05.

RESULTS

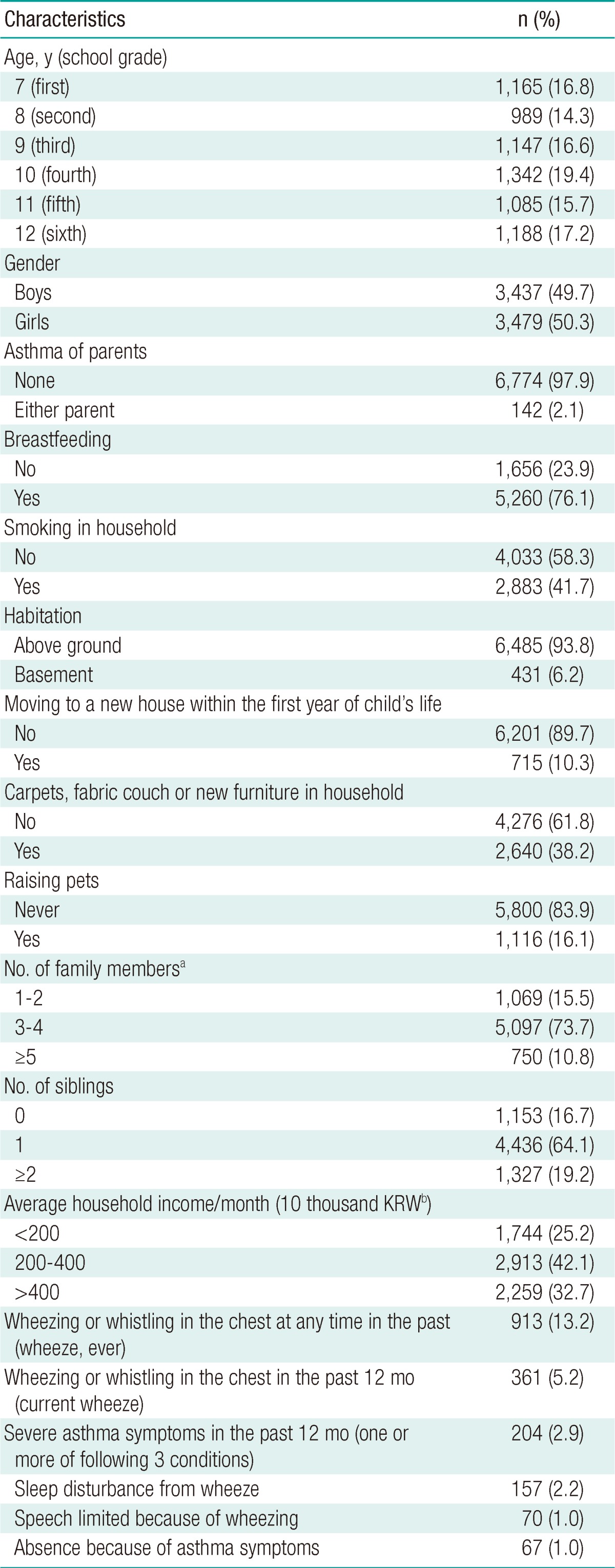

The demographic and environmental characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1. There were 1,342 (19.4%) fourth grade children (10-years-old), and 989 (14.3%) second grade (8-years-old) children. There were 3,437 (49.7%) boys. The subjects with no siblings numbered 1,153 (16.7%). There were 1,744 subjects (25.2%) who had average monthly household income of <2 million won, and 2,259 subjects (32.7%) who had average monthly household income of more than 4 million won. There were 913 (13.2%) subjects who had experienced asthma symptoms at any time in the past, and 361 (5.2%) subjects had current wheeze. There were 204 subjects (2.9%) with severe asthma symptoms in the past 12 months.

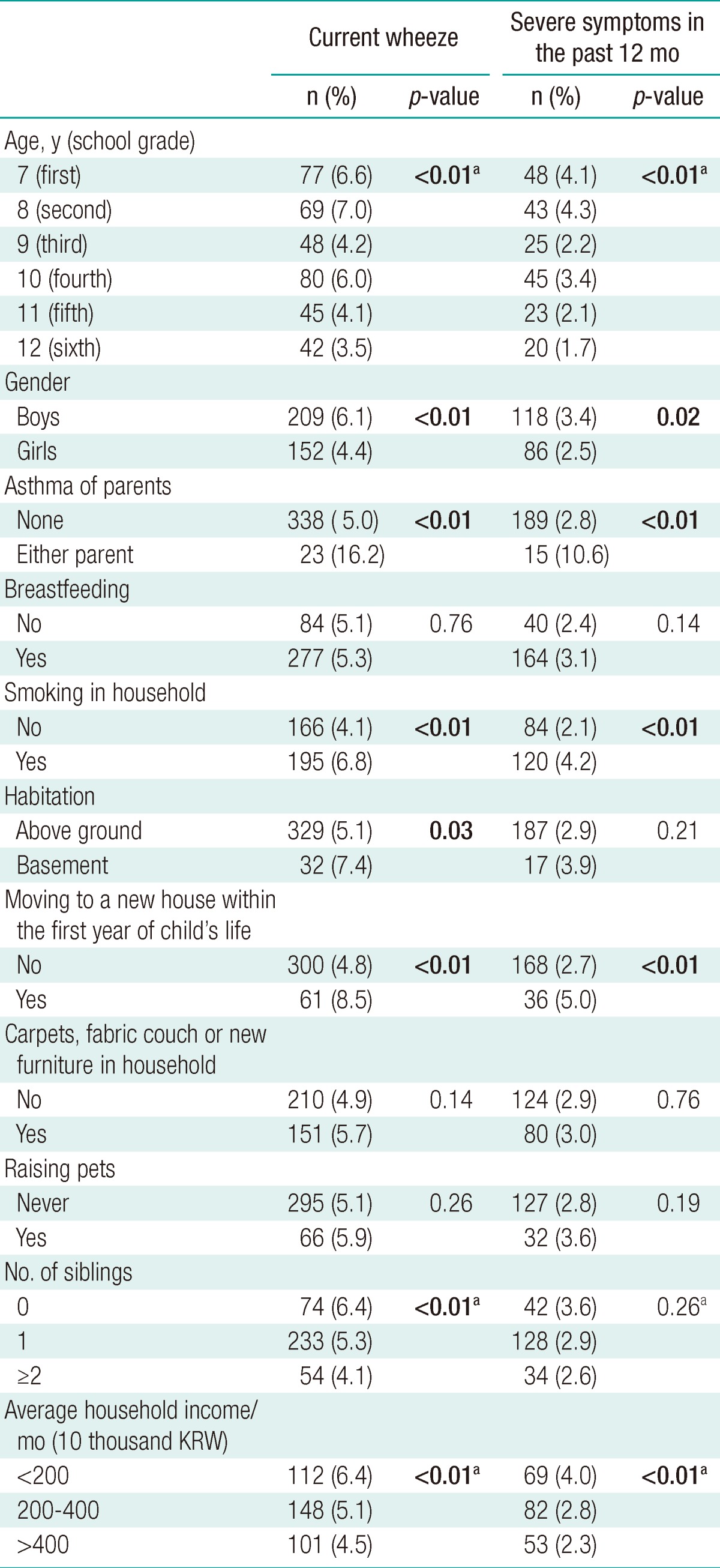

The results of the chi-squared tests (associated factors with asthma symptoms) are presented in Table 2. Current wheeze was inversely associated with age (p for trend<0.01) and positively associated with boys (p<0.01), parental history of asthma (p<0.01), smoking in the household (p<0.01), living in basements (p=0.03), and moving to a new house within the first year of a child's life (p<0.01). The number of siblings (p for trend<0.01) and average household income (p for trend<0.01) were inversely associated with current wheeze. The results showed an association between severe asthma symptoms and these associated factors, although there was no significant association between living in basements (p=0.21) and the number of siblings (p for trend=0.26).

Chi-squared tests for factors associated with current wheeze and severe asthma symptoms in the past 12 months

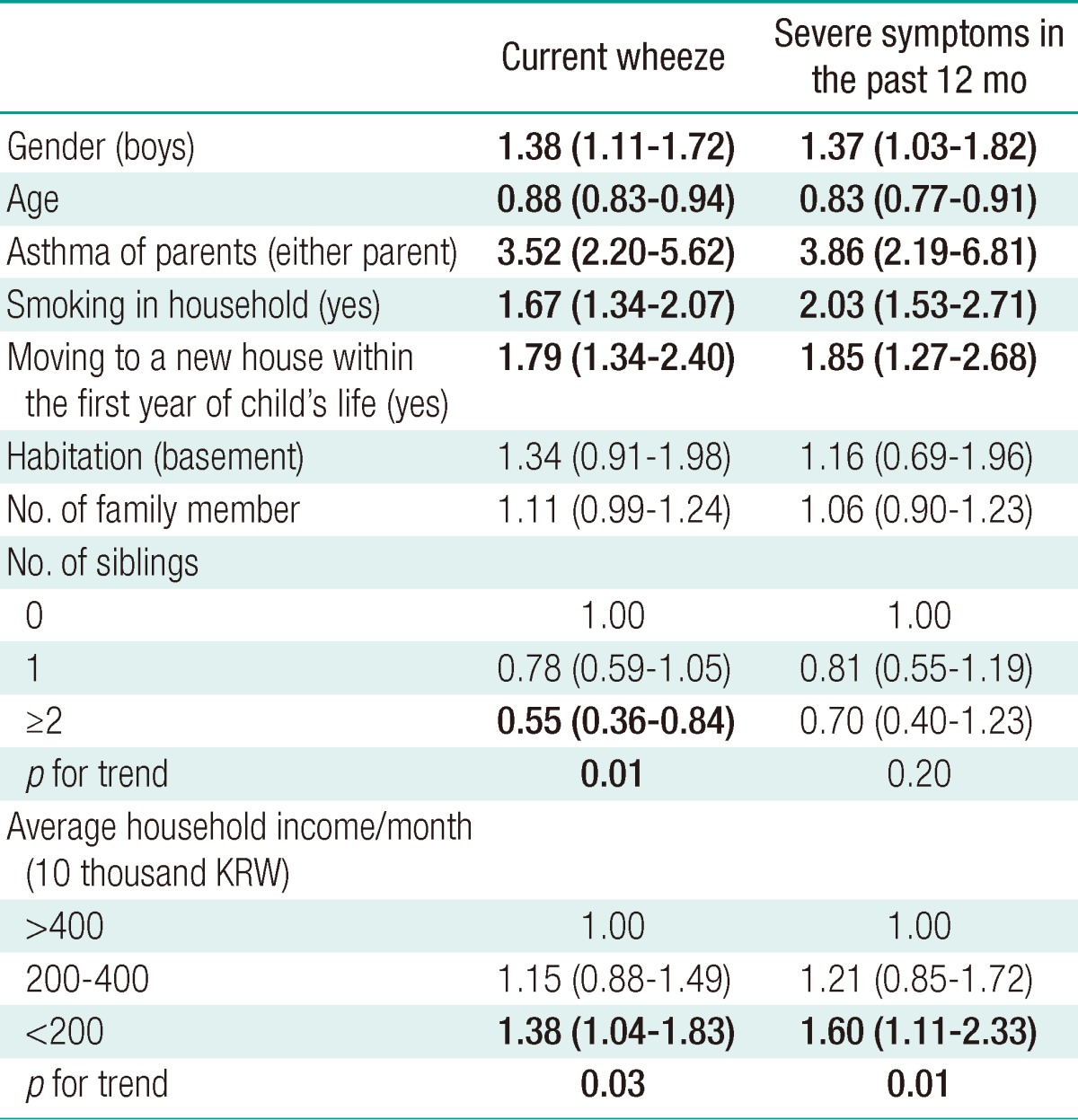

In the multiple logistic regression analysis, average household income was inversely associated with current wheeze after adjusting for gender, age, parental history of asthma, smoking in household, moving to a new house within the first year of a child's life, habitation, the number of family members, and the number of siblings (Table 3). The OR for average household income <2 million won per month was increased 1.38 times compared with an average household income of >4 million won per month (95% CI, 1.04-1.83). The trend for inverse association was statistically significant (p for trend=0.03). Similar results were obtained for severe asthma symptoms in the past 12 months.

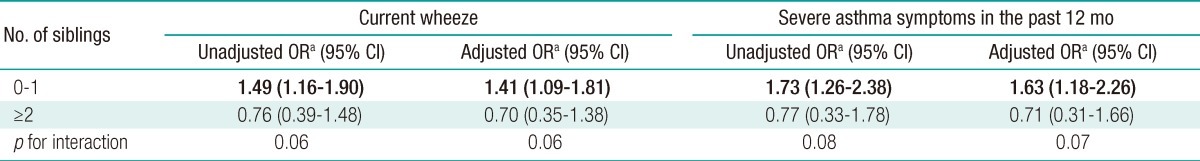

There was a marginally significant interaction effect between the number of siblings and average household income on current wheeze (Table 4). When a child had fewer than 2 siblings, the odds ratio for average household income <2 million KRW per month increased 1.41 times compared with an average household income of ≥2 million KRW per month (95% CI, 1.09-1.81, from the multiple logistic regression models with an interaction term). However, the effect of low income was attenuated and not significant when there were 2 or more siblings (OR 0.70; 95% CI, 0.35-1.38). Additionally, similar results were obtained for severe asthma symptoms in the past 12 months.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the prevalence of wheeze in the past 12 months and the association between household income and asthma symptoms in elementary school children. The prevalence of current wheeze (wheeze in the past 12 months) was 5.2%. Household income and asthma symptoms were inversely associated after adjustment other potential risk factors. This association was modified by number of siblings. For children with two or more siblings, the effect of household income on asthma symptoms was not significant. However, low household income was still a significant variable for patients with fewer than two siblings.

According to an official report from the ISAAC phase three Seoul center, the prevalence of current wheeze was 6.5% among children aged 6-7 years [13]. Based on a random sample of school-age children, Suh et al. [2] reported that the prevalence of 'wheezing, last 12 months' was 5.9% for boys and 4.2% for girls in a metropolitan area. These values are consistent with those from this study; the prevalence of current wheeze in Korean children has slightly decreased recently [14].

There are many indicators of SES that are used in health research. Income measures the material source component directly and is considered to be a suitable indicator of material living circumstances [15]. Using equivalent income, which is calculated by applying equivalent scale to household income, is a preferred method of considering household income as an indicator of SES [16]. However, household income adjusted for the number of family members is another good method [16,17]. In this study, average household income adjusted for the number of family member was considered to be an indicator of SES.

Household income was inversely associated with current wheeze in this study. This result is consistent with the results of previous investigations; there is an inverse association between SES and childhood asthma [18,19]. Hafkamp-de Groen et al. [18] reported that low household income levels and maternal education levels were risk factors for wheezing after age 1. The increased risk of wheezing in children of low income family continued at age 4 (OR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.06-2.22). Ruijsbroek et al. [19] reported that the prevalence of asthma increased as SES decreased.

Exposure to unmeasured vulnerable environment for asthma and family stress may be possible explanations for these findings. Schaub et al. [20] reported that exposure to endotoxin and infections increased among children in low-income families. Celedon et al. [21] showed that exposure to endotoxin in later life increased the risk of atopy, although exposure in early life protected against the occurrence of atopy. Kozyrskyj et al. [22] showed that chronic exposure to a low-income environment was associated with persistent asthma. In their study, chronic low-income status was associated with both family stress and high exposure to endotoxin. Several studies support that exposure to parental or caregiver stress in early life was associated with increased infantile levels of proinflammatory cytokines for asthma [23,24].

Sibship size is reported as a protective factor against allergic diseases [25]. However, causal factors explaining the sibling effect are still unclear. In addition to the hygiene hypothesis [26], the in utero programming hypothesis has recently emerged [10]. In allergic reactivity, T lymphocyte responsiveness is an important condition. T-helper 1 (ITh1) cells cause the secretion of IgG antibodies and remove allergens [27]. To protect against the rejection of the maternal unit, fetal immune response is skewed to Th2 phenotype. Hygiene hypothesis conceptualizes the failure of immune maturation as a reduced adequate exposure to external environments [28]. However, the in utero programming hypothesis pays attention to the maternal immune system and the in utero environment during pregnancy. The fetal immune system development appears to be affected by maternal exposure to allergens [29-31]. Additionally, it seems that certain endocrine disrupting substances play a role in this development. Reichrtova et al. [32] found an association between placental contamination and organochlorine and increased levels of total IgE in newborns. Schade and Heinzow [33] reported that the level of certain persistent organic pollutants, including organochlorine, was negatively associated with parity. These finding supports the in utero origin of the sibling effect [34].

In this study, the association between low-income and asthma symptoms was modified by the number of siblings. Although the underlying mechanism is unclear, the role of stress on asthma and the moderation of stress might be possible explanations. Previous studies reported that child or maternal stress level was inversely associated with SES [35,36], and stress may increase the risk of asthma in children through a stress-induced Th2 immune response [37,38]. As mentioned above, maturation or modulation of the immune system may be a suggested underlying mechanism of the sibling effect. In this study, the adverse effect of stress on asthma symptoms caused by low SES may be buffered or moderated by the sibling effect. However, this interpretation should be performed with caution because of the small number of cases included in the analysis. Number of children who simultaneously had household incomes <2 million KRW per month and >2 siblings were 54 in the 'current wheeze' cases and 34 in the 'severe asthma symptoms' cases.

This study has several strengths. We used a questionnaire that was based on the ISAAC core module, which is considered to be a standard questionnaire worldwide. Conducting a web-based survey, we made an effort to collect household income data as truthfully as possible. The study sample was quite large, and the subjects were from relatively homogenous regional backgrounds. Additionally, we excluded preschool children because wheezing in preschool age children might be more frequently associated with respiratory infections rather than with asthma [39].

There were some limitations of the study. Determining the causal relationship might be difficult because this was a cross-sectional study. However, it seems unreasonable that the status of children's asthma affected household income or SES, particularly considering the national health insurance system of Korea. The study sample was not random. Perhaps it is difficult to directly apply these results to general elementary school children in Seoul. Although generalizability depends on whether the underlying biological mechanism of the relationship between the exposure and outcome is the same between two populations [40], further evaluations should be performed to improve the generalizability.

In this study, socioeconomic status was a determinant of asthma symptoms in childhood. It seems that childhood asthma disparity is dependent on household income. Therefore, policies improving childhood health inequities should be emphasized.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Seoul Medical Center, Research Institute. We appreciate the Korean Academy of Pediatric Allergy and Respiratory Disease, which provided the official Korean version of ISAAC questionnaire.

Notes

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare on this study.

This article is available from: http://e-eht.org/